Bouarfa v. Mayorkas

Amicus Curiae Brief

A “friend of the court” or amicus, brief is filed by someone not a direct party to the case, but who has an interest in its outcome. These briefs seek to supplement the merits briefs by offering the Court additional arguments and information. Amicus briefs can be filed at the merits stage or at the certiorari stage.

What's at Stake

Whether a U.S. citizen gets a day in court to challenge the federal government’s revocation of her spouse’s immigrant visa.

Summary

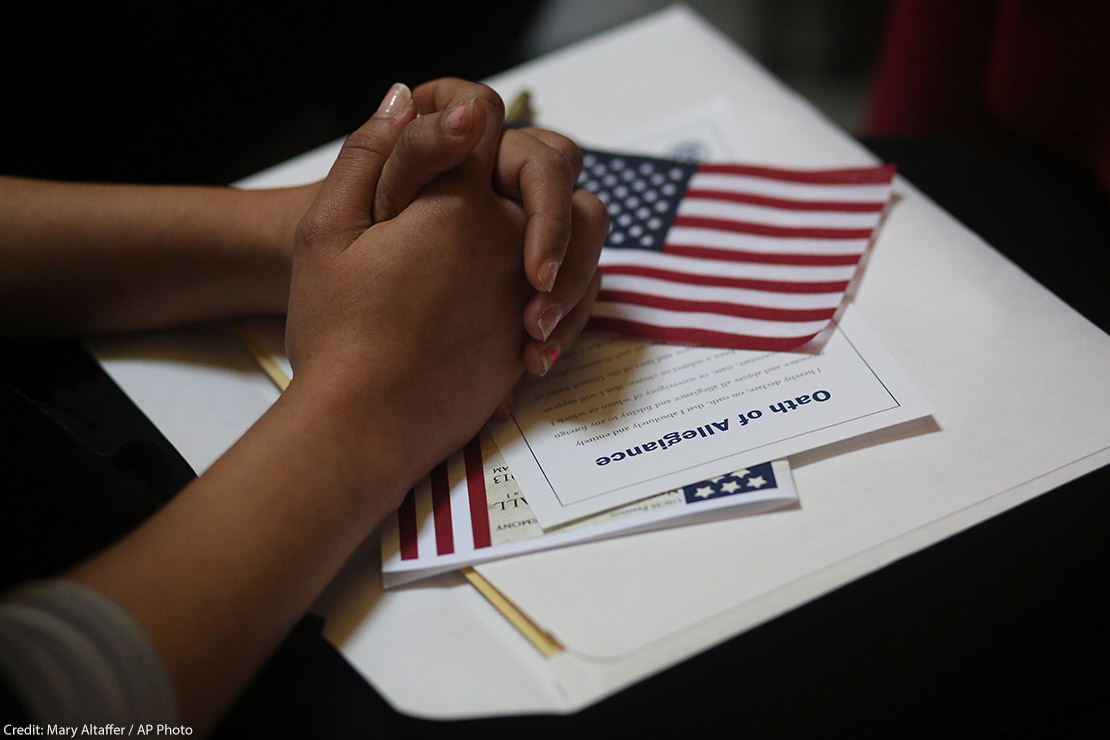

For many noncitizens, the road to citizenship begins when a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident family member files a visa petition on their behalf. That was the case for Ala’a Hamayel, whose wife, Petitioner Amina Bouarfa, a U.S. citizen, filed a visa petition for him. United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) approved Ms. Bouarfa’s visa petition, allowing her husband to live lawfully in the United States with her and their children and providing him with a pathway to citizenship. But years later, the agency revoked the visa petition, asserting that Mr. Hamayel’s prior marriage had been a sham—a conclusion based on testimony from Mr. Hamayel’s ex-wife that she later recanted. Ms. Bouarfa challenged the agency’s decision to revoke the visa petition.

This case presented the question whether visa petitioners can ask a federal court to review an agency’s decision to revoke a visa petition. Long settled Supreme Court precedent establishes that federal agency actions are presumptively reviewable by federal courts. Indeed, if the agency had denied Ms. Bouarfa’s visa petition in the first instance, everyone agreed that Ms. Bouarfa would have been able to challenge that decision in federal court. But the government argued that the decision to revoke Ms. Bouarfa’s visa petition was not reviewable because of a statute that bars federal-court review of (i) “any judgment regarding” certain enumerated forms of immigration relief and (ii) “any other decision or action” specified to be in the discretion of the agency. According to the government, clause (ii) covered the agency’s sham-marriage decision.

Because this case required the Supreme Court to interpret clause (ii), this case raised the concerning possibility that the Supreme Court might apply Patel v. Garland, a previous decision that greatly expanded the scope of clause (i) to include nondiscretionary decisions, to clause (ii) as well, expanding its scope to include nondiscretionary decisions. Our brief explains why that would be mistaken, and why clause (ii) applies only to discretionary decisions—not any and everything related to those decisions. Had the Court come to this conclusion, the consequences could have been devastating for noncitizens and their families. Immigration agencies are overburdened and serious mistakes by agencies happen. Noncitizens and their families have long relied upon courts to correct those mistakes. But if clause (ii) were expanded to preclude review of nondiscretionary decisions, federal courts would be barred from even considering whether a mistake occurred in many immigration proceedings. Immigration agencies’ decisions have life-altering consequences; noncitizens and their families deserve, at minimum, the opportunity for a fair day in court.

In its decision, the Supreme Court concluded that clause (ii) prevents federal courts from reviewing an agency’s ultimate decision to revoke an approved visa petition, but, in line with the amicus brief filed by the şěĐÓĘÓƵ, the Court never addressed the issue of whether clause (ii) prevented review of nondiscretionary decisions, explicitly leaving that issue open. Thus, although the Court concluded that the courts lacked the authority to review the visa revocation in this case, the Court did not issue a sweeping decision that would prevent judicial review in many other cases. And notably, noncitizens like Mr. Hamayel who have their visa revoked and later re-apply for a visa may get federal court review if their new visa application is denied.

Legal Documents

-

07/10/2024

Amicus Curiae Brief in Support of Petitioner -

12/10/2024

Bouarfa v Mayorkas Decision

Date Filed: 07/10/2024

Court: United States Supreme Court

Date Filed: 12/10/2024

Court: United States Supreme Court