Surveillance Supporters Tout Police Audit Logs But They’re Not an Effective Check and Balance

When law enforcement deploys powerful surveillance infrastructures (for example face recognition, drones, and license plate readers) they’re often accompanied by requirements that officers log their usage, typically including various details about the technology deployment as well as its purpose. These are often touted as important checks and balances that should make people feel okay with the surveillance. But audit logs that depend on self-reporting by officers and departments are not an adequate check on the enormous power that surveillance technologies place in their hands.

This has come into especially stark relief recently with the driver surveillance company Flock. The company has been facing a lot more political opposition lately because of reports (first by and subsequently by many ) that its database of license plate scans from thousands of communities around the nation had been accessed by Trump Administration immigration authorities, and by a department in Texas looking for a woman who’d had an abortion.

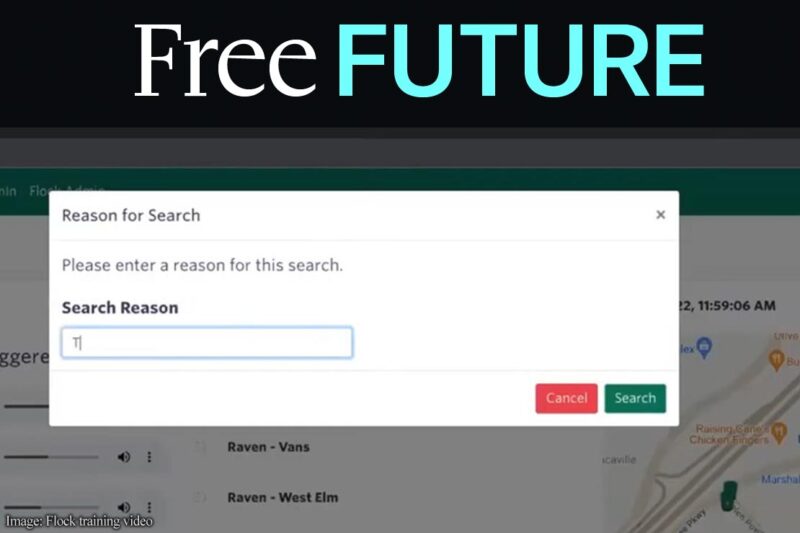

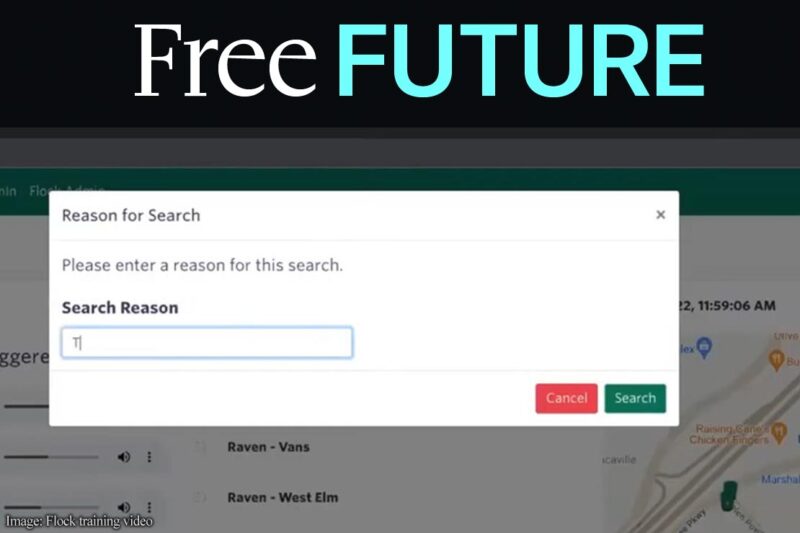

Those cases came to light because officers doing searches with Flock’s software fill out a field describing the purpose of that search, and that purpose description is preserved permanently in the audit trail of every agency whose camera was included in the search. So if you’re in Anytown Police Department and share your data nationally (as do 75% of Flock police customers ), you see the searches by a police department of Texas, and every other department that has done a nationwide search that has included your data, and all of their stated reasons for each search. 404Media and other reporters have searched through local department audit records and found thousands of searches tagged with terms like “ICE,” “immigration,” and “deportee” as well as the abortion search.

Vague and misleading terms

The problem with all of this audit logging is that there isn’t any mechanism to make sure the logs are accurate and meaningful, and a lot of reasons to doubt that they will be. Many officers just enter vague and brief explanations for searches, like “investigation,” “crime,” or “missing person.” The Electronic Frontier Foundation (which has also this problem) that within a dataset of 11.4 million Flock nationwide searches in a six-month period, more than 14% of the searches fields contained just the word “investigation.” My colleagues at the şěĐÓĘÓƵ of Massachusetts, who used open-records laws to obtain records from police departments across the state, a similar pattern of vague descriptions.

While Flock’s audit logs have been successful in bringing to light certain abuses, that very fact is likely to deter many officers from honestly describing the purposes of their searches moving forward. Take the controversial Texas abortion search. If the officer who logged, "had an abortion, search for female" had just left out the word "abortion” that story never would have seen the light of day. And there’s no doubt that the department — and police around the nation — realize that.

Text messages between local police and federal agents serving together on a task force and obtained by reporters at the site already reveal at least one officer bemoaning negative consequences flowing from using the word “immigration.” One officer texted,

Hey guys I no longer have access to Flock cause Hutch took my access away . Apparently someone who has access to his account may have been running plates and may have placed the search bar “immigration”.. which maybe have brought undue attention to his account.

The bottom line is that the public simply can't count on these kinds of logs to be a reliable check against the enormous power that its mass surveillance system is placing in the hands of law enforcement.

Supporters of mass surveillance tout logging as a genuine check on power

Despite these problems, companies and local police officials facing skeptical city councils and members of the public tout this purpose-logging as a significant check and balance.

Flock , “To underscore accountability, every single search conducted in the Flock LPR system is saved in an audit report…. This is part of our commitment to transparency and accountability from the beginning of the design process.” But the company pretends that purpose logs are more real than they are. In response to the abortion-search controversy, for example, Flock that

Following this event, Flock conducted an audit of all searches conducted on Flock LPR and found not a single credible case of law enforcement using the system to locate vulnerable women seeking healthcare.

What they mean is that they found not a single case where a law enforcement officer had logged an abortion search as such.

Not only does Flock tout audit logging as a serious accountability measure, it is also relying on such logging to comply with state law. Illinois bans out-of-state police from searching state license plate databases for immigration offenses, gender affirming care, and abortion. In response, Flock that it had “released a new feature to automatically flag and exclude any search of Illinois camera data with terms that indicate an impermissible purpose.”

At least one political leader isn’t buying it. In July, Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden, who has been conducting oversight on Flock, that he’d reached an agreement with the company to filter out any requests for Oregon driver-surveillance data that, according to the log, were related to abortion or immigration, as it was doing in Illinois and other states. This month, however, Wyden declared that upon further investigation, he had determined the agreement was “meaningless.” In an October Wyden told the company,

Flock agreed to apply software filters to data collected by cameras in Oregon… However, subsequent oversight by my office revealed that these filters are easy to circumvent and do not meaningfully protect the privacy of Oregonians.

Overall, he declared,

it is my view that Flock has built a dangerous platform in which abuse of surveillance data is almost certain. In particular, the company has adopted a see-no-evil approach of not proactively auditing the searches done by its law enforcement customers because, as the company’s Chief Communications Officer told the press, “it is not Flock’s job to police the police.”

In an attempt to answer critics, Flock has to providing an option for police departments to require officers to also enter a case number for each search. But case number requirements have the same problem as purpose descriptions: they can too easily be faked or “accidentally” entered incorrectly. Civil rights attorneys report that police officers sometimes enter incorrect case numbers when logging body camera footage they want to bury so that that footage, while not illegally deleted, gets lost in the system.

In addition, case-number logging is a poor transparency measure. Case numbers are internally assigned by the police department and without additional records (like the investigative file), it won’t be apparent what the underlying investigation is about. And it’s not practical to expect any member of the public or the press to file public records requests to get the case files for every case listed in an audit log.

Two things that should both be true

I’ve been discussing this problem in the context of license plate readers, but purpose-logging is touted as a check on abuse for other technologies as well. The problem first came to my attention in the context of police “drones as first responder” (DFR) programs. Researching these programs for a 2023 , I saw that while had commendably adopted the practice of publishing the time, purpose, destination, and precise route of every DFR flight, I also noted that when it came to the purpose field, many were missing or vague — a problem, I said, that “should be fixed.”

But it’s actually not easy to imagine how the problem would be fixed. There don’t appear to be any widespread standards for what a meaningful “purpose description” looks like, or reliable managerial and disciplinary structures to back them up. And we live in a country where independent, effective oversight of police departments is exceedingly rare. The of police departments controlling officers who fail to use their body cameras, for example, is not promising.

To be clear, none of this means that we think companies ought to remove logging, case-numbers, or other auditing features. They always have the potential to help inform the public; many officers will be honest and police managers can mandate the inclusion in audit logs of all important details, try to require meaningful responses, monitor compliance, and discipline those who don’t comply. But when log entries threaten to stir up controversy, throw a department into the headlines, and provoke political opposition to technologies they badly want to acquire, we just can’t count on any of that happening. It’s also true that if your local police department shares records of where you’re driving, it has zero control over the practices of other agencies across the nation that are searching your data.

Ideally, two things would both be true: 1) logging should be a standard, expected practice, with rules in place to maximize the chances it will be meaningful; and 2) nobody should be impressed by this practice or lulled into thinking it’s a sufficient counterbalance to the awesome surveillance powers new technologies can convey.